There is perhaps a false problem with the now fashionable debate on meritocracy, which started with brushed-up neo-Confucianist tenets and pretended to challenge the “Western” rules of democracy (electing people like Trump or Berlusconi as heads of government) by promoting “Asian” values of merit and virtue, which picks people with moral values and great learning.

As a former student of Mozi’s, who first opposed the Confucians in the 4th century BC, I may be biased, but I think the debate is confusionist, not Confucianist.

“Meritocracy” per se is nothing special; the whole world uses it. The Chinese first had it, then from the 16th century, thanks to the Jesuits’ translations, it was adopted in Europe, and from there, the whole world employed it, now calling it “bureaucracy.”

The problem is not the meritocracy but the selection of the top leader. A bureaucracy is selected, in fact, by someone above who chooses the criteria for selection, but who chooses the chooser? Historically in China, it was the emperor. He became emperor because he inherited the title or staged a coup, a revolution, or an invasion.

It was the same in Europe, and the passage from one ruler to the next was always a problem, never smooth.

In Europe, the Church mediated the selection of the heir by approving or rejecting the first son or fixing the rules of succession: only the firstborn (no matter if male or female) or only the first male.

In China, the rule was the emperor had to choose among his many sons; the more sons, the better the selection. There was no Church mediation and meddling, but there was court intrigue to support this or that son.

Incidentally, Qing emperor Kangxi (1654-1722) was close to the Jesuits in his court and possibly was interested in converting to Christianity. He eventually didn’t because the Church demanded that he have only one wife and his first son as his heir. It would have changed the imperial succession rule and invited the Church into the heart of Chinese politics.

There was never a smooth transition of power, and often massive drama, bloodshed, and turmoil.

With the invention of modern democracy (let’s even give it a derogatory name, “ballotocracy”) and its sedimentation in apt institutions, the transition of the top power, president or prime minister, is pretty smooth: Whoever wins the elections gets the top job.

In return, there is a constant low-intensity drama in the permanent political campaigns, but (with rare exceptions) no major butchery and mayhem. It creates a very predictable environment for businesses that can see what is coming (this or that president) and often ignore the change on top because there would be no significant change in policies or none without early public warning in the public debate.

Now who chooses the top leader in modern China?

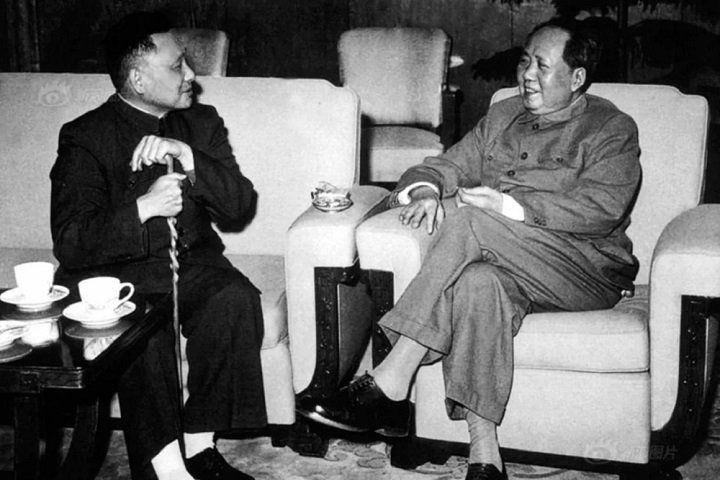

Mao took power through a very dramatic revolution, Deng through what amounted to a coup, and from then on, things haven’t been smooth.

In 1997, shortly after Deng’s passing, the party tried to set rules for a smooth transition. It didn’t work out. It introduced the regulation of retirement at 68, specifically designed to push Chairman of the Parliament Qiao Shi into retirement. He agreed to have it for a fluid changeover requiring then-president Jiang Zemin to retire fully in 2002, ceding his seat to Hu Jintao. It was supposed to be an orderly power transfer from one generation to the next. Yet it didn’t work.

Qiao’s influence was eliminated after 1999 when he was accused of “negligence” about the Falun Gong, and Jiang didn’t fully step back in 2002; in fact, he was still powerful and influential until 2012, when Xi Jinping became party secretary and president in March 2013.

We had a decade of political confusion because the agreed rules were not respected. Then, in 2022, Xi dropped the rule altogether, again creating a new environment.

Historians can discuss for years what went wrong between 1997 (when the rule was set) to 2002 (when the rule was broken) and why, despite some hope at the beginning after 2002, there was a fallout of power order.

Still, the result is that the top leadership succession has been messy in China and will continue to be so unless a different structure is put in place.

It isn’t a good long-term environment for businesses that like lasting political stability and predictability. This “prejudice” became especially true after three years of Covid and the Ukraine invasion, where Beijing first sided with Moscow.

It is not about meritocracy but the peaceful passage of people on top of the meritocratic system and its vast consequences. Here China has unsolved problems in practice and philosophical studies.