American rules or Chinese respect. The meeting may be a turning point in the confrontation of the two powers while post COVID diverging economic policies set them farther apart.

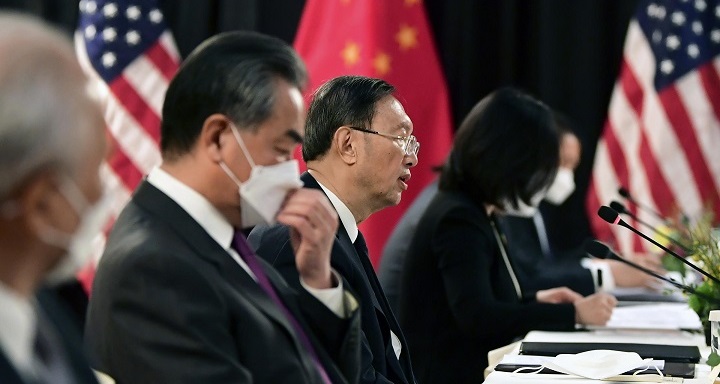

At the Anchorage meeting, the US declared it has long-term goals for China and was not seeking short-term trade deals. The United States wants for China democracy, ending the oppression of minorities, an end of grand territorial claims, and also the end of coercion of American allies. For these issues, there are no easy fixes. China was upset by this agenda, which was for the first time brought clearly into the open. In the past, these concerns were voiced in back channels or in the newspapers, but not openly on the table at negotiations.

Therefore, Anchorage sets a new pattern for an ongoing relationship. But even more important was the way the US chose to frame these discussions.

By raising all these issues, it accused China of not following international rules, and by objecting to the long reply made by the head of the Chinese delegation State Councilor Yang Jiechi, it posed a problem. The two sides had agreed to two-minute opening speeches, and Yang Jiechi, apparently offended by the American remarks, offered a twenty minutes speech about American faults and destabilizing role in the world.

With this, the American side said basically: yes, we have many problems, but we face them openly and clearly. We don’t brush them under the rug, as China does, and besides China agreed to a two-minute opening speech and went on for twenty minutes. That is, China is unreliable and doesn’t follow its own commitments.

Before the meeting, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken was in Japan and South Korea. The timing was not accidental. The United States wanted to make sure it had the backing of its two most important Asian allies. By meeting first with allies and framing the discussion as based on rules and not based on state-to-state requests, the United States de facto said: China is posing an issue to the whole world, not just to us, and we will confront China on behalf of our interests and on behalf of the interests of the world. That is, the United States apparently dropped old hopes that trade, globalization, and welfare will distribute well-being equally to the whole world, and will gradually change China.

The US says China doesn’t follow the rules, and therefore the game is not fair, so we have to fix the game. To this, China replied by saying basically we want respect, and the United States is in no position to preach to us about democracy and oppression when there is oppression and distortion of the rules in America.

China refused to respond to accusations about the rules, and therefore, according to the United States, China’s not following international rules. In this way, China is going down a risky path. By not responding and not accepting the discussion on the rules, and not following the rules (on talking time), China apparently tacitly admits that indeed it is not following the general rules. Moreover, by asking for respect, rather than a discussion on the rules, it tells the United States and the world that international discussions shouldn’t be based on international norms and regulations, but on the issue of mutual respect between states. This may be right but it is a hazy conception.

Rules and laws can be debatable, but they can also be clearly defined. They can be thwarted and bent by force, but they are still there. Respect is much hazier: what is respect, what is the respect you ask for, and do you give the same respect to small states and larger states? Bigger states want more respect? And what do you do with smaller states? Do you yell at them, and push them around? These are all hazy issues that sound well and good for the Chinese domestic audience but in the international arena have little traction.

The world may have objections and reservations about how the United States uses laws and rules for self-serving purposes, but the issue of respect seems defined just to serve Chinese national interest versus anybody who infringes on them. There is no objectivity and no standard that can be used internationally and fairly for everybody, at least in theory, like rules and regulations.

Rules or Respect

By framing the controversy with the United States as an issue of respect, China goes down a path that the world has already known. The Soviet Union didn’t recognize the rules and regulations set by the United States and the Western world during the Cold War, and therefore discussions were just on minor issues about what could be settled together to have a minimal coexistence.

With China, of course, it’s not the same as the Soviet Union. The claims are not the same, the world is different and the country is not the same. Yet by framing the issue around respect rather than laws and regulations, China refuses the discussion as framed by the United States.

This leaves China with a few different choices: it can accept the neo-Cold War model whereby the two have just minimal agreements and agree to disagree on many important issues. Therefore, there would not be cooperation but an adversarial relationship between the two countries. This would split the world and tear it apart, and eventually isolate China.

On the other hand, China can try to force or persuade the United States to accept and frame bilateral relationships based on respect. It is a possibility, but at the moment seems very unlikely because the United States feels that it went down this road for forty years and it brought little tangible results. Therefore, to turn the tables again by persuasion will be extremely difficult, and if it is done by force, well, that means something like a war.

Both cases at the moment seem very unlikely. China may also choose to ignore the differences and pretend they are not there, but if this is so, discussions will be arduous between the two sides, to the point that it could be just perfunctory, while tensions continue to build up.

Another choice would be for China to accept a discussion based on rules and regulations. This can be done also in several ways, such as in a legalistic manner by arguing every dot and point and therefore de facto ignoring the main facts and irritating the United States. It can also be done by accepting that China has something to change. This of course is an extremely sensitive point that touches on many issues internally.

There are no easy solutions.

Diverging economic policies

This happens on the backdrop of an unprecedented split of financial policies. During the Cold War, capitalism and and de facto central banks acted on their own in the two worlds.

After the end of the Cold War, Wall Street swept the world with two major financial crises, one in 1992 in Europe and one in 1997-1998 in Asia. In both cases, Wall Street managed to get its way: in 1992 by breaking the European monetary system, and in 1997-1998 by causing the fall of most Asian economies. In both cases, the victory proved somehow short-term.

The fall of the European monetary system prompted European countries to stress European coordination and push them to have the euro, the new currency which de facto limited the power of the US dollar. In Asia, the bureaucratic and legal barriers protecting the full convertibility of the Chinese currency, the renminbi, prevented the crash of the renminbi and the Hong Kong dollar and prompted the rise of China’s suspicion of the USA.

By resisting Wall Street speculation, the Chinese managed to make a few friends in Asia, become convinced of the necessity of protecting their own currency, and postpone the full convertibility of the renminbi, which had been set initially for the year 2000 and now over 20 years later is nowhere in sight.

Setting Wall Street completely free through pure financial means didn’t bring a stronger dollar. It brought about fears of an unbridled financial market that would ignore all kinds of other issues. That is, financial markets by themselves without a political drive were deemed very dangerous, both in Europe and in Asia.

This sense was also reinforced with the 2008 financial crisis. In fact, since the launch of the euro, policies were coordinated among the European Central Bank; the American central bank, the FED; and gradually also the Chinese central bank, with the support also of the Japanese and the English central banks. This coordination was even more evident during the 2008 financial crisis, where the large Chinese stimulus was welcomed by the whole world because China’s recovery helped global recovery.

However, at this moment the American and European central banks—plus those of Japan, the UK, and other developed countries—are all in agreement on the need for an extremely large stimulus package that will relaunch the global economy at the risk of rekindling inflation. Inflation had been dormant since the 1980s—since the supply-side economy gave the world 40 years of monetary stability.

Now in this exceptional historical moment, the West is willing to give up its caution and risk inflation, thinking that the benefits of a fast recovery far outweigh those of the social damages brought by inflation.

However, China is different now. Unlike in other times when its economy was tiny compared to those of the United States and Europe, this time Beijing GDP is huge. China also had its stimulus in 2008, and in fact, in 2020, when China managed already to have its recovery driven by exports. Its economy was churning out products, medical and non-medical, when factories all over the world were almost shut down. That is, demand for goods from the rest of the world primed the Chinese economy.

Then, China doesn’t need a stimulus package, and certainly doesn’t need it in the way Europe and America do. In fact, China fears that with this large stimulus package, it will be forced to import inflation from abroad as it is pushed to adjust the exchange rate of the renminbi to keep its exports competitive, and markets could become very volatile bringing possible damage to Hong Kong directly linked to the global markets. Any choice here is tough and controversial.

The Chinese population is extremely historically sensitive to inflation. In 1988 then Party Secretary Zhao Ziyang was brought down by internal critics after his price liberalization started a wave of inflation. Adjusting the exchange rate is also controversial because it would bring greater competition with other developing countries that have convertible currencies and therefore economies that can be cornered by Chinese exports.

This will cause greater tensions between China and neighboring developing countries. China would then exacerbate its controversies not only with the developed world but also with the developing world.

Or Stagflation and the world order crumbling down

Of course, there is also the problem that financial stimulus may not work, and that there could be deflation and stagnation in the rest of the world. Rather than spending more, people would hoard money thinking that the future is bleak, and the prospects for the coronavirus and political situation were uncertain. In that case, the economy won’t pick up and there won’t be inflation. But in this case, China wouldn’t go scot-free either because if the world doesn’t buy goods that includes not buying Chinese goods.

In fact, no matter what happens with the stimulus, the vaccines will return some normalcy to global production, and people will grow less dependent on Chinese exports. Therefore, yes, China will not be hit by inflation but may be hit by dwindling exports.

The issue of rules and regulations on the background of these diverging economic policies between the United States, Europe, and China could feed on one another. Divergences on rules, trade, human rights, territorial claims, and coercion can be exacerbated by differing economic policies and a tottering global economy.

Here, also we have a third, extremely delicate element. Many countries have internal difficulties, and we won’t go into each of them. But simply in Russia, the rule of Vladimir Putin is wobbling. The economy is not faring well, the cities are rallying around dissident Navalny, and allegedly even Putin’s people are unhappy about his 20-year rule.

He may want to seek peace in the many open fronts he has with the West, which are bleeding his economy, but it’s not clear how he will achieve that, if ever.

Iran, for a long time a huge issue in the Middle East, has not improved its economy or its internal situation, where the rule of the ayatollahs continues to be controversial.

North Korea has a very unclear internal situation. What happened to Kim Jong-un a year ago is still shrouded in mystery, the role of his sister has been raised to unprecedented heights, and only one thing is clear: North Korea is more controlled by China, and therefore China will have to answer for Pyongyang’s future’s misbehavior.

In Myanmar, with protests mounting, there is no clear end in sight, body counts are piling up, and no one knows how this will end. China is caught in this Myanmar trap, siding with the generals and unable to guide them or find a solution.

The National League for Democracy wants power and the military ousted, and there seems to be no room for compromise. China is strategically dependent on the pipeline that goes from the Bay of Bengal to Yunnan. It is strategically important for China, as it bypasses the Straits of Malacca and avoids the bottleneck of the South China Sea, which is full of tension and extremely volatile.

In India, which has significant border tensions with China, there are internal debates on the new direction of prime minister Narendra Modi.

The United States is equally divided and basically no issue but China brings the country together.

With all these fronts open, and with these huge divergences on economic policies and international politics, it’s extremely easy for something to go wrong, and there is no positive sign in sight.

An American BRI?

These Chinese difficulties in theory create a huge unprecedented opportunity for the United States to start to rebuild a world order—without China, if China disagrees, or with China, if China agrees to the rules.

In the past, China managed to challenge the US prominence with the Belt and Road Initiative, by setting itself at the center of industrial production and having an idea of railway and transportation infrastructure that could reach the whole world.

The idea could have been totally successful if China at the same time agreed to accept the existing set of political and commercial rules, and if it decided to very actively seek the cooperation and leadership of the United States.

With that strategy, China would have poised itself as the successor to the leadership of the existing world, and the United States might have eventually agreed to that, provided that rules and regulations would be followed. There could have been a succession of the kind we had seen between Great Britain and the United States.

However, China acted as if it was already the first country in the world, barged into the global order, ruffled many feathers, and created hostility all around. The United States now is left with this legacy: what to do with the world?

The United States cannot carry on as if the Belt and Road never existed, as if the alliance of democracies and technologies will be enough to cordon off China and prevent its rise.

The United States is offered an opportunity to reshape and revamp the rules of this world, and the good reception of China’s Belt and Road Initiative shows that there is the necessity to build a network of infrastructure that could foster development in the globe in the next 20 or 30 years.

People and goods want to move better and faster, and the United States may have the future technology, such as the hyperloop, which would increase the speed of transportation in all the world. If this is done by the United States rather than China, it would further isolate China and bring it to the negotiating table.

All these elements are clear and open for China to consider. Does China want to challenge the world, or does it want to adapt to the world? Is it so sure that America is declining or vice versa that it is not seeing a vice hanging over its neck? China is on the cusp of momentous decisions.

For this, China needs to decide carefully and know full well the pros and cons.

Here, there is a final element to consider. At the Anchorage meeting, was the Chinese side fully aware of the situation? Yang looked taken by surprise by the American opening statement. Yet it was hardly a secret America would be polite but straight with China. Is there a short-circuit in the Chinese information system?

Deceived by one’s own propaganda

There is a crucial issue about who decides what is appropriate, solid-information news versus fake news. Ultimately the issue can be divided into two choices: either the state decides or the media companies and the journalists decide.

If the state decides, of course, it can control the message and this can be beneficial to the stability of the state: purging inconvenient news and destabilizing facts, and choosing what will appear in the end supports stability. One can see that this is actually beneficial to the overall stability of the state, which benefits the common people and guarantees security.

However, when the state controls the information to use it for propaganda purposes, this can also create other difficulties or a short circuit.

It is difficult to set up an independent, effective, and true reporting system, reporting news to the head of state. The head of state needs effective news reporting to face whatever challenges and threats may arise in the state. However, if the system is totalitarian—if the central government controls all information—it is difficult for the reporters to tell the truth.

Reporters’ promotions, salaries, and wellbeing will be dependent on the happiness of the government, their client. And in an atmosphere where the news media peddles propaganda, it is even more difficult for internal information agencies to tell the truth.

That is, if you use information as a propaganda tool, this will naturally spread and contaminate the internal information network on which the government depends to meet whatever challenges happen from within or without the state.

A situation in which the media and journalists are fully responsible for what they write and report creates a conversely different environment, in which information agencies are spurred by the competition to tell the truth and to tell it before other outlets.

The state knows the accurate situation inside and outside, and therefore in theory can meet whatever challenges and threats they happen to have.

The downside of course is that the government is potentially constantly under attack by the media and there is de facto a division about the sense of what is good for the state.

In a country where the state controls information, the political survival of the head of state is paramount and in reality coincides with the survival of the state.

In a system where there is a free press, media outlets can have different opinions on what should be done for the state, and therefore the survival of the state may not correspond to the survival of the head of state or the survival of a given government.

There is a duality that creates on one hand constant tension but overall long-term stability because the possible fall of the head of state doesn’t mean the fall of the government or of the state itself.

This may be also behind what happened in Anchorage on March 19th.

= has francesco sisci gone over to the dark side and becomes a pax-americana apologist or propagandist ??? this is a truly surprising and disappointing piece by a “sinologist” who is also a Beijing-based Senior Research Associate at China Renmin University. the central theme of the long-winded few thousand words here are nothing but an attempt to admonish china for not respecting and obediently kowtowing to the US and its many “rules”. the way that FS distorts and frames china’s demanding for “respect” as a big-power ego trip appears to be utterly willful and malicious in trying to cast china as a delinquent, irresponsible global citizen.

FS seems to be intentionally ignoring the facts that the rather unspoken “rules” set by the US and its many allies have precipitated any number of wars, devastations, deaths and misery around the world for decades and its still happening this very day in syria, yemen, libya, iraq, iran, cuba etc etc.

perhaps the good FS would be kind enough to enlighten the world with some good, well defined details as to what really are these “international norms” or “rule-based orders” so strongly advocated the US and himself instead of referring to them with such vagueness and obfuscation.

furthermore FS’ unquestioning acceptance of the hk “democracy”, xinjiang “genocide”, “forced labour” narratives is especially incomprehensible and grating to have come from a “china scholar”. so far no one has produced any solid, irrefutable evidence to these chinese “crimes” besides some weird photos of men in blue shirts, fenced up buildings or words of some “activists” under the payroll of the CIA-NED, the name Rushan Abbas rings a bell ??? so far all the accusations, “reports” etc against china were centrally based on some hearsay first manifested by one adrian zenz, a German far-right fundamentalist Christian who proclaimed himself to be the god anointed warrior of justice for the uigur chinese. no, this adrian zenz has never set foot in xinjiang or anywhere near there in his entire life.

Who sets the world order everyone has been talking…the Western powers?

United States “negotiations” with China in Alaska should be interpreted as a soft surrender agreement to China. In losing the tech war, trade war, and covid war to China, United States must negotiate its surrender. Not in Washington DC, which would be unconditional surrender to China. Not in New York, which would be complete surrender in finance and trade. But in Alaska to a soft surrender agreement. In the history of war, the losing side always surrenders on home soil after the defeat. Germany in Berlin, Japan in Tokyo Bay, Napoleon in Paris, all surrendered on home soil. This Alaska “negotiations” is no difference. It is what it is, an American soft surrender to China.

Your last article was excellent but way too long. You had ideas in there that would’ve made to and possibly three different articles. I think your analysis is useful and it’s a good contribution To our Understanding of this relationship . However it is way too long. It combines two or maybe three ideas that could have

Been the basis for separate articles. I disagree completely with the comment above. I don’t know anything about the commentor but I don’t think he/or she is open minded

US built the Rules-Based Internatonal Order after 1945 in which the first rule is that US writes the rules and rewrites them as it sees fit. That gave us the Pax Americana and scores of wars, anong them a dozen years of war against Vietnam, now twenty years trying to stabilise a puppet regime in Afghansistan. It also gave us regime change , in Iran in 1953, in Chilli in1973 and dozens more. It gave us the dollar as international currency which allowed US to pay for imports with dollars created out of thin air. It made the Middle East into an unholy mess. And it left its own infrastructure in a dilapidated state. It wants to be respected as the suzeraign over all other countries.

China is a revisionist power. It wants to go back to the norms of the Westphalian Peace Treaties of 1648 and the Charter of the United Nations. It needs to be productive, as do other countries, and is providing itself and other countries with modern infrastructure.

US is spending more on “defence” than the next six countries together. Even so China looks to be well able to deter US aggression.

And what else has US to offer? Democracy? The policies of the administrations of successive presidents are hardly different. At this time the Republican party is the party of Apartheid while that was the policy of the Democratic Party until president Johnson. US has a Fake democracy.

Just a few relevant remarks

Thank you fro writing this. As I read his article his whole argument about “rules based” anything with the United States is so transparently propagandist I went looking for where he originally published so I could leave a comment. The United States for 74 years now has been behaving like the author of this comment describes: “The first rule is that US writes the rules and rewrites them as it sees fit.”

Jesus Christ Francesco, you needn’t waste all the ink you do on every single one of the screeds you publish, when you could just write out the central thesis that binds them together: China should bend the knee to American Hegemony, because reasons. Save us all, and yourself, the time.

This is a fantastic, well thought out, and on-point piece. Thank you!!