Il testo che pubblichiamo in traduzione italiana è il frutto di una conferenza di Francesco Sisci all’Università Link a novembre del 2017, voluta dai professori Vincenzo Scotti e Marco Meyer. «In generale per il mio lavoro con la Chiesa cattolica in Cina devo ringraziare Carlo d’Imporzano e Francis Yan, i quali mi hanno costantemente spinto a interessarmi della questione, specialmente le tante volte che per sconforto di varia origine avrei voluto lasciar perdere. A loro questa conferenza è dedicata».

I rapporti tra Santa Sede e Cina sono una questione estremamente delicata e anche piena di sfumature, però nonostante questi dettagli importanti e delicati, sono sostanziati da un binario di pensiero strategico sia da parte cinese sia da parte della Santa Sede. Ciò che vediamo è una maratona in cui due percorsi strategici molto diversi, due modi di pensare molto diversi stanno man mano convergendo e questa convergenza è la maggiore senz’altro dal 1949, da quando il partito comunista ha preso il potere, e i rapporti Cina – Santa Sede si sono prima scollati poi completamente staccati.

Forse oggi i punti di convergenza strategici a lungo termine sono i maggiori mai avuti nella storia tra Santa Sede e Cina, le due forse uniche istituzioni millenarie sul pianeta.

Prima di andare sui millenni partirei dalla cronaca cioè da quella che è stata l’accelerazione degli ultimi due anni. In questo periodo c’è stata un’accelerazione molto molto forte, che ci fa ben sperare per il prossimo futuro. Visto che queste istituzioni pensano in termini di secoli o di decenni, naturalmente non sappiamo dove e quando si arriverà a una normalizzazione dei rapporti, potrebbe essere tra un mese, tra sei mesi, tra un anno o tra sei anni. Però c’è stata un’accelerazione.

La visita del 2015

Il primo punto di svolta di questa accelerazione credo sia avvenuta quasi casualmente durante la visita in contemporanea negli Stati Uniti a settembre del 2015 del papa e di Xi Jinping. In quell’occasione Xi Jinping si aspettava – come successo come con le visite di tutti i suoi predecessori – che l’America in qualche modo si spegnesse e si concentrasse sulla visita del presidente della Cina.

Era un periodo molto delicato di campagna elettorale molto tesa e dura, tra Hillary Clinton e Donald Trump però il passato era stato una testimonianza forte, e avevano steso i tappeti rossi, le prime pagine dei giornali americani si erano concentrate sulla visita cinese e sul futuro del rapporto fra Cina e stati Uniti.

In quel caso stranamente successe un’altra cosa poiché c’era la visita del papa. Il papa doveva andare a parlare alla sessione plenaria delle Nazioni Unite. Per circa 40, 50 giorni la visita di questo papa, oscurò da una parte il dibattito politico statunitense, cioè si parlava più del papa che di Trump e Hillary, e d’altro canto oscurò Xi Jinping.

Questo fatto fece capire in modo concreto quello che alcuni in Cina dicevano già da tempo, ma in qualche modo non era percepito dalla leadership, cioè il super potere “lieve” del papato, del Vaticano.

La Cina negli ultimi 20-25 anni ha capito che c’è una dimensione soffice nella potenza e nella proiezione internazionale di una superpotenza, quella che Joseph Nye chiama soft power e c’è questo interesse negli ultimi 20, 25 anni della Cina sulla proiezione del soft power. Lì, nella visita del papa in Usa, c’è stata un’esplosione del soft power. È stato questo che ha fatto vedere come prima di tutto la questione Cina-Vaticano non era semplicemente una questione interna, di gestire 10, 12, quattro milioni di cattolici che vivono in Cina, ma un problema molto più complesso. Era il problema di avere un rapporto con la super potenza lieve del mondo, cioè la Santa Sede.

Se la Santa Sede riusciva a imporsi e coprire il dibattito interno americano questa era la vera super potenza soffice. Naturalmente questo ha avviato un cambiamento della dinamica dei rapporti bilaterali e sul modo di pensare il dialogo tra Santa Sede e Cina, che per altro già avviato da molto tempo. Soprattutto, ha cambiato i tempi, il senso di urgenza. Se la questione Santa Sede – Cina era solo interna, la Cina la considerava sì una questione importante ma alla fine della giornata i cattolici non creano problemi sono una minima minoranza. Cioè è una questione che si può risolvere domani, dopodomani, senza nessuna urgenza. Se invece la Santa Sede è la super potenza il pensiero diventa: noi cinesi, che dobbiamo inserirci in questo mondo dove il Vaticano riesce ad essere così importante. Dobbiamo avere un senso di urgenza.

Secondo, arriva anche un calcolo di rischio. Se il Vaticano è così potente, non si tratta più solo di gestire questi pochi milioni di cattolici cinesi. Questi possono forse aiutarci ma forse anche danneggiarci nella nostra posizione nel mondo. In tal mondo la questione è stata posta in termini totalmente diversi rispetto a come era pensata la questione precedentemente.

L’intervista

Da lì è nata man mano l’ipotesi di fare un’intervista al papa che doveva essere un messaggio che i due leader si scambiavano e soprattutto doveva uscire fuori anche dai confini, dai profili ovvi della situazione.[1] Cioè il papa come si è visto, come era già chiaro, non era semplicemente interessato alla sorte dei cattolici, non parla solo dei cattolici; il papa, questo papa, è interessato alla sorte di sette miliardi di esseri umani, e ne è fortemente interessato. Lui non pensa solo al suo orticello di un miliardo di cattolici battezzati, lui pensa a tutti.

Ciò è molto importante perché lui ha parlato in quella intervista ai cinesi delle questioni che stanno a cuore ai cinesi. Ha parlato da prete, da buon prete. Ha parlato come un prete che da bambino – ricordo – quando capitava un guaio, riusciva a trovare le parole che colpiscono il cuore e ti convincono a ripensare a quello che hai fatto. Questo approccio ha convinto anche i cinesi, e credo che abbia posto la questione Cina – Vaticano su termini diversi non semplicemente su termini ideologici, non solo strategici geopolitici ma di supporto di aiuto umano. C’era quello che la Chiesa poteva fare per i singoli cinesi che hanno tantissimi problemi materiali ma hanno dei problemi di coscienza molto forti, ad esempio la questione del figlio unico.

I cinesi adorano i figli e i figli sono un problema fondamentale, la continuità con gli antenati, quasi come una religione dei figli, il fatto che i cinesi hanno deciso negli ultimi trenta anni di non avere figli, di sacrificare, di uccidere “il loro dio” in qualche modo pur di crescere, di trasformarsi, di cambiare è la testimonianza, da una parte di quanto siano determinati a cambiare di mettersi in una strada diversa.

D’altro canto la vicenda del figlio unico è evidenza di quanto essi abbiano sofferto e soffrono per questi cambiamenti e il papa lì è riuscito a trovare le parole per guardare in avanti, non per tormentarsi e continuare a tormentarsi. Quindi questa è stata una cosa molto importante, e l’intervista credo sia uscita molto bene, tanto che, poche ore dopo che l’intervista era stata rilasciata, i giornali cinesi l’hanno ripresa. Ci sono state centinaia di riprese. Non l’hanno tradotta totalmente ma ne hanno dato notizia.

Un dettaglio molto importante è che l’intervista è stata data in inglese, non in italiano, non in cinese; l’inglese è stata l’unica versione ufficiale perché serviva una lingua neutra, che capisse il papa e che capisse contemporaneamente Xi Jinping. È un aspetto cruciale per la mia modesta esperienza di cronista; le traduzioni sono sempre un trucco, sempre molto delicate specialmente tra italiano e cinese e viceversa, lingue culturalmente e strutturalmente molto diverse. Quindi ogni volta non si tratta di fare una traduzione meccanica, ma di rendere un pensiero da una parte e dall’altra. Ed in questa resa di pensiero ovviamente mille pezzi si perdono da entrambi i lati. Perciò era importante avere un mezzo neutro che avesse la stessa valenza da un lato e dall’altro, e l’inglese è una lingua che ormai sia il papa e Xi Jinping sono in grado di capire senza ulteriori mediazioni.

L’afflato sentimentale

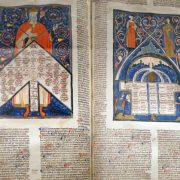

Questo è stato il primo punto di rottura e di avvicinamento concreto, cioè l’illuminazione di settembre 2015 si è trasformata in un primo atto di convergenza importante. Un secondo atto, un “annusamento“ direi è stata una visita a marzo 2016 del vicepresidente esecutivo della scuola del partito che è venuto a Roma, ha incontrato tanta gente e ha “annusato“ la situazione ed è rimasto sbalordito dei Musei vaticani della cultura e dello spessore di questi. Un altro elemento molto importante: è rimasto incuriosito che nei Musei vaticani ci fossero anche tante sculture e opere cinesi, perché la Santa Sede considera questi tesori parte della storia della Santa Sede e dell’umanità, e della testimonianza dell’amore della Santa Sede per la Cina.

“Amore” è una parola un po’ forte che non si usa in geopolitica, eppure una parola molto importante per la Chiesa e per la Cina, un paese politicamente molto scettico ma anche molto sentimentale. Per affrontare la Cina ci vuole un afflato sentimentale e se c’è questo afflato sentimentale tante difficoltà si superano; senza di questo tante difficoltà invece sorgono e si moltiplicano; la percezione di questo sentimento verso la Cina è stato un elemento molto importante.

In quei mesi poi Gianni Valente aveva intervistato per Vatican Insider alcuni vescovi cinesi “sotterranei”. Tutti avevano espresso il loro appoggio a un accordo con Pechino. Cioè: la Chiesa cinese più fedele al papa nei decenni voleva l’accordo, non era contraria.

Tutto questo ha aperto la strada a uno snodo importante, arrivato ad agosto del 2016 quando il cardinale titolare di Hong Kong, John Tong, ha pubblicato sul settimanale diocesano un lungo saggio ecclesiologico che apriva concretamente sui termini di un accordo tra Santa Sede e Cina. L’accordo non era impossibile, ma c’era uno spazio concreto per il bene della Chiesa in Cina che non doveva essere più lasciata da sola. La questione dei vescovi poteva essere risolta.

Un intervento così dotto, umano e autorevole, significava che non c’era in realtà opposizione sostanziale a un accordo.

A fare da cassa di risonanza e creare un nuovo consenso anche in Cina sulla questione, poi ci fu il lavoro in quei mesi il Global Times, il giornale semiufficiale, nato da una costola del Quotidiano del Popolo, voce della leadership cinese. Il Global Times ha pubblicato quattro articoli[2], una enormità rispetto all’esperienza del passato.

Ad agosto poi per la prima volta nella storia dei rapporti bilaterali il presidente cinese Xi ha risposto al messaggio di un papa e ha mandato in dono una copia della Stele cristiana di Xi’an del VII secolo. Da sottolineare che già Paolo VI negli anni ’60 scrisse a Mao. Da allora in poi tutti i papi, più volte, hanno scritto ai leader cinesi, senza alcun effetto. Xi per la prima volta rispondeva con un oggetto che intendeva dire: il cristianesimo non è una religione occidentale arrivata in Cina di recente, ma è parte da secoli della tradizione cinese, come l’altra grande religione oggi dominante nel paese, il buddhismo. Questi è arrivato in Cina sempre intorno a quegli anni.

Il discorso del segretario di Stato

Un’altra data importante nel 2016 è stato il discorso del segretario di Stato Pietro Parolin per Celso Costantini. Questo è stato un discorso assolutamente fondamentale per Pechino, perché Parolin è naturalmente segretario di Stato e naturalmente un uomo che ha seguito la questione in primissima persona, la questione Cina, per circa venti anni, che ha conosciuto bene i cinesi e ne ha conquistato la fiducia operando da prete e non tanto da diplomatico. Lui si poneva non come politico, ma come prete, e questo lungi dall’allontanare gli interlocutori invece li ha avvicinati. Cioè lui aveva sottolineato un aspetto diplomatico politico che però aveva questa sostanza di essere sacerdote.

Perché Celso Costantini è importante? Per due elementi, per prima cosa lui rinunciò a essere nominato cardinale facendo nominare cardinale per la prima volta un vescovo cinese e questo dimostrava che la Chiesa non voleva imporre un controllo del clero romano sulla Chiesa cinese e anzi la Chiesa romana voleva che la Chiesa cinese fosse veramente cinese. Anzi era importante che il primo cardinale cinese non fosse lui, che era italiano trapiantato in Cina negli anni ’20, ma fosse un cinese vero. Quindi era un messaggio politico molto importante per la Cina.

Seconda cosa, estremamente importante dal punto di vista politico per la Cina, Costantini lottò per avere un riconoscimento del ruolo della Santa Sede con una prima nunziatura indipendentemente e lontano dal ruolo della Francia.

La Chiesa cattolica era sostanzialmente uscita dalla Cina dopo che era stato abolito l’ordine dei gesuiti, eravamo a metà del ‘700, e dopo esserci entrata alla fine del ‘500. Rientrò circa un secolo dopo, nel 1856 con la seconda guerra dell’oppio proprio portata dalla Francia che era allora la potenza tutelare della chiesa. In questo contesto con l’esempio di Celso Costantini Parolin volle affermare che la Santa Sede, anche se non ha uno stato come lo stato pontificio alle spalle, non vuole agire per conto di o sotto una potenza egemone. Quindi si trattava di un messaggio molto importante perché naturalmente c’è il dibattito in Cina, su: ma per chi si muove la Chiesa? si muove per le nuove potenze attuali? si muove per essere di aiuto? è su spinta degli Stati Uniti, dell’Europa, dell’Italia?

No, il messaggio di Parolin è che la Santa Sede si muove in proprio e non vuole potere, non lo ha voluto allora non lo vuole adesso. Quindi la Santa Sede parla da sola non parla attraverso lo Stato, quindi questo è stato un punto molto importante per definire aggiungere un lato politico.

La conferenza all’Università Remnin

Un’altra tappa di questa accelerazione è stata una conferenza organizzata dall’università del popolo a Pechino il 29 ottobre nella Renmin University. Essa è un’università un po’ particolare. Ci sono tre grandi università in Cina, ci sono molte grandi università, ma l’Università di Pechino è famosa per storia, letteratura, filosofia, materie umanistiche. Poi c’è la Qinghua, famosa per le materie scientifiche tra cui l’economia, e la Renmin che invece è l’università fondata da Mao Zedong, fondata dal partito, l’Università del popolo che si interessa in particolare di questioni politiche e di legge, le questioni più delicate.

Dunque che l’Università Remnin facesse una conferenza su questioni religiose era estremamente delicato ed importante. In questa conferenza i cinesi hanno espresso pubblicamente una parte assolutamente importante e fondamentale a livello storico dei rapporti secolari della Chiesa. Loro hanno detto attribuendolo a Parolin, quindi in questo senso sottolineando l’importanza che i segretari di Stato hanno nei rapporti bilaterali, che la leadership cinese avrebbe accettato il ruolo del papa nella nomina dei vescovi.

Questa cosa in Italia, in Occidente oggi sembra ovvia. In realtà sappiamo che è stata spinosissima per secoli. Anche da noi la storia dei vescovi-conti è quello che ha dato forma ai rapporti tra Sacro romano impero germanico e papato. L’imperatore tedesco che si inginocchia davanti al papa a Canossa raccontano appunto i sussidiari di storia.

In realtà questo punto fondamentale non era stato risolto dai gesuiti nemmeno quando i gesuiti con von Shall o Verbiest erano diventati parte della corte imperiale come ministri molto importanti dell’impero. Eppure nonostante il potere e l’influenza di questi gesuiti, storicamente celebrata, neppure loro erano riusciti ad ottenere dall’imperatore il privilegio per il papa nel nominare i vescovi.

Ciò perché l’imperatore allora sommava potere politico e poteri quasi religiosi. Viceversa con l’adozione del marxismo come ideologia di Stato il potere politico cinese si è distaccato dalla dimensione metafisica. Il Partito comunista cinese è materialista e non ha nessun interesse nelle questioni ultra mondane. Quindi si apriva uno spazio teorico di convergenza, molto importante perché entrambi i sistemi lavorano in termini “teologici” deduttivi: prima bisogna fissare i principi e poi dai principi trarne delle conseguenze.

C’era uno spazio per un accordo vero, profondo, il partito non si interessa di Dio, si interessa delle questioni umane. Il papa, il papato, la Chiesa si interessa di questioni di cui il partito non si interessa, di Dio. Si apre veramente una possibilità di una convergenza come non c’è mai stata tra poteri imperiali cinesi e papato e la comprensione anche della particolarità e dell’originalità della fede cattolica.

Le ragioni di un’incomprensione

C’era un problema in Cina di incomprensione profonda della particolarità della Chiesa cattolica che da un parte parla italiano, parla latino, parla inglese eccetera, cioè è radicata profondamente nelle varie realtà nazionali. Ma è anche universale e cattolica, cioè appunto comprensiva di tutto, diversamente da Chiese protestanti o ortodosse che sono molto più radicate nelle specificità locali a discapito della dimensione generale.

Questo passo avanti di comprensione in Cina, estremamente significativo, è avvenuto in uno specifico contesto. Siamo a ottobre del 2016, verso la fine della campagna elettorale americana e l’interesse cinese verso la questione della Santa Sede non è solo più interno ma in relazione a tutto il contesto internazionale. Il contesto internazionale portava a concentrarsi naturalmente sui candidati alla presidenza, Hillary Clinton o Donald Trump. Allora molti cinesi pensavano che la presidenza Trump sarebbe stata migliore per i rapporti bilaterali della presidenza di Hillary Clinton.

In realtà dopo le elezioni si è visto che non è stato così. O forse sarebbe stata la stessa cosa con la Clinton, non lo sappiamo. Ma di certo la presidenza Trump ha portato ad un avvelenamento progressivo, anche molto rapido dei rapporti bilaterali. Questo ha influenzato il rapporto con la Santa Sede perché credo che la Cina abbia capito che la Santa Sede non si faceva influenzare e non seguiva a ruota gli americani. Essa continuava a mantenere la sua rotta strategica indifferentemente da quello che potevano fare, pensare, dire gli Stati Uniti. D’altro canto, il potere e l’influenza della Chiesa continuava a crescere.

In tutti questi mesi è sembrato che il potere di influenza della Chiesa abbia preso una nuova dimensione. Essa pare vada anche a penetrare alcune lacune lasciate aperte dal potere americano che ha problemi di crisi e di riadattamento ad un nuovo mondo dopo circa 16 di disastri dalla guerra in Iraq e Afghanistan passando per le primavere arabe e la guerra in Siria. Politiche che hanno dissanguato l’economia americana e hanno approfondito il caos in Medio Oriente e Asia centrale.

L’annuncio della possibile normalizzazione

Questo ha portato ad un piccolo passo avanti, una cosa che è stata molto sofferta. L’8 marzo 2017 i cinesi hanno mandato in onda una prima trasmissione televisiva sulla rete ufficiale in cui annunciavano la possibilità di una normalizzazione delle relazioni. È stata una cosa molto problematica. Doveva essere prima in un giorno, poi in un altro, è stata rinviata. Alla fine è stata fatta, ed è stata una cosa dialettica. I cinesi dicevano: ma la Chiesa ha rovesciato e aiutato a rovesciare il regime comunista, in Polonia, è stata quella che ha distrutto l’Unione sovietica, quindi, sottintendevano, farà la stessa cosa in Cina.

Nella trasmissione, si è stato obiettato, sì da una parte è successo, ma forse anche perché in quei Paesi c’erano carenze specifiche e debolezze molto forti di quel sistema. Però contemporaneamente la Chiesa in quegli anni ha salvato Cuba, che per molti versi poteva essere molto più a rischio della Polonia o della Russia. Il regime castrista è stato salvato per un intervento molto forte fatto dalla Chiesa cattolica a favore dei Castro. Ciò dimostra che quindi la Chiesa non ha programmi ideologici non ha agende politiche. Anzi è una prova che la Chiesa guarda il mondo in termini ampi e non ha una prevenzione anti comunista di principio. Certamente è contraria all’ateismo, vuole maggiore libertà religiosa però ha salvato Cuba.

Questo dibattito in televisione anche molto animato ha messo in evidenza i dubbi e i timori che continuavano a perdurare in Cina su questo tema.

Così il 1° giugno c’è stato un altro passo significativo. Il fondo di investimenti culturale, guidato da Zhu Jiancheng, è venuto a donare un quadro al santo padre e l’idea che abbiamo visto si è sviluppata è cresciuta. Siamo nel 2017; è in programma una mostra congiunta, da una parte dei Musei vaticani a Pechino e dall’altra il Museo della città proibita a Roma presso i Musei vaticani. L’idea è stata lanciata a loro e recentemente a novembre 2017 c’è stato l’annuncio da parte della televisione cinese e dal Global Times che la diplomazia dell’arte è equivalente alla diplomazia che portò alla normalizzazione dei rapporti fra Cina e Stati Uniti negli anni ’70.

Quindi ciò ha voluto dire che a novembre 2017 abbiamo avuto la “rottura del ghiaccio“ ufficiale, cioè la dichiarazione politica da parte della Cina che c’è la volontà politica di normalizzare i rapporti, naturalmente ancora non sono normalizzati ma è stato annunciato che c’è la volontà politica di farlo – quando saranno normalizzati e se lo saranno –; ci sono questioni aperte e fatte di molti dettagli. Bisogna mettere a punto mille questioni anche di diffidenza, mille paure delle due “amministrazioni”, ci sono prudenze da entrambi i lati.

La Cina deve pensare a novanta milioni di membri del partito, alla stabilità e ai rischi che stanno aumentando sempre di più giorno dopo giorno con le tensioni attorno alla Cina stessa. D’altro canto la Chiesa deve pensare come una decisione del genere può essere digerita e vissuta dal resto della Chiesa mondiale tra cui ci sono i cattolici, ma non solo, vista l’influenza globale su sette miliardi di terrestri.

Pochi giorni dopo c’è stata la visita del papa a Myanmar, una visita molto seguita in Cina perché il papa andava quasi in Cina. Myanmar inoltre è uno dei paesi con cui la Cina ha rapporti politicamente più stretti. Il papa ha affrontato la questione dei Rohingya che occupano un’area dove i cinesi potrebbero volere creare un loro porto e un oleodotto strategico. Qui i cinesi in realtà hanno una linea molto coincidente con quella del papa e con punti di vista maggioritari nell’amministrazione in America.

I cinesi speravano che il papa desse un sostegno al leader democratico del paese Aung Saan Suu Kyi, volevano limitare il potere dei militari. I cinesi hanno sempre avuto dei rapporti molto stretti con Aung Saan Suu Kyi anzi l’hanno sostenuta e protetta in tempi molto delicati e sono favorevoli ad una transizione democratica positiva della Birmania. Non solo non vogliono i militari tiranni, ma non vogliono scontri di piazza che dilanino il Paese. Il papa è riuscito a parlare bene sia ai militari sia ad Aung Saan Suu Kyi, sia ai buddhisti. Infatti, in Myanmar c’è un fondamentalismo buddhista molto radicali e molto anti musulmani.

I cinesi sono stati molto soddisfatti da questo, tanto è vero che per la prima volta il Global Times ha dedicato un articolo a questa visita del papa, e un gruppo di sacerdoti cinesi con tanto di bandiera nazionale sono andati alla messa del papa alla cattedrale di Yangoon dicendogli: venga presto santo padre.

Naturalmente il “presto” dei tempi cinesi potrebbe essere due mesi come due anni, però ormai il punto importante, è questa accelerazione. Essa continua anche in questi giorni, nonostante, e forse proprio a dispetto del coro di critiche che si è levato da una parte della stampa internazionale contro tale eventualità.

China-Vatican: The eve of a possible agreement

Relations between the Holy See and China are a very delicate situation, which are full of nuances, however nonetheless these important and delicate details are substantiated by a binary strategic thought process, by both China as well as the Holy See. What we see is a marathon in which two very diverse strategic paths, two very different ways of thinking, are gently converging, and this convergence is the greatest since 1949, since the Communist Party came to power and the relations between China and the Holy See were first disengaged and then completely disconnected.

Maybe the strategic points of conversion today, are the greatest there has ever been in the history between the Holy See and China, possibly the only two millennial institutions on the planet.

Before moving on to milleniums, I would start from the news, from the acceleration which took place over these last two years. During this period there has been a very powerful acceleration, which makes us hopeful for the near future.

Seeing that these institutions think in terms of centuries and decades, we naturally do not know where and when a normalisation of these relations will come about, it could be within a month, six months, a year or six years. However an acceleration has taken place.

The 2015 visit

The first turning point in this acceleration, I believe came almost casually, during the visit to the United states of both the pope and Xi Jinping, in September 2015. On that occasion Xi Jinping expected – as had happened with all the visits of his predecessors – that America, in some way, would ‘switch off’ and concentrate on the Chinese president’s visit.

It was a very delicate period during a very tense and hard electoral campaign, between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, however the past was a strong testament, and they had brought out the red carpet, the first pages of the American newspapers were concentrated on the Chinese visit, and the future of the relations between China and the United States.

At that time a strange coincidence came about, since the pope was also visiting. The pope was to go speak at the plenary session of the United Nations. For around 40, 50 days the visit of the pope, obscured the United States’ political debate, or rather the pope was talked about more than Trump and Hillary, and on the other hand he obscured Xi Jinping.

This fact helped the Chinese leadership understand in a concrete way, that which several in China had been saying for some time, that is, the “soft” superpower of the papacy, of the Vatican.

In the last 20-25 years, China has realised that there is a soft dimension in the power and international projection of a superpower, that which Joseph Nye calls soft power, and China has been interested, in the last 20-25 years, in the projection of soft power. During the pope’s visit to the US, there was an explosion of soft power. It was this that showed how, first and foremost, the China-Vatican question was not simply an internal matter, of managing 10, 12, four million Catholics living in China, but a much more complex problem. The problem of having a relationship with the soft super-power of the world, that is, the Holy See.

If the Holy See was able to impose itself and eclipse the American internal debate, this was the true soft superpower. Naturally, this had initiated a change in the dynamics of these bilateral relations and the way of thinking about the dialogue between the Holy See and China, which had already been set in motion for quite some time. Above all, this changed timescales and the sense of urgency. Even if the question of the Holy See – China was only an internal one, China considered it an important issue, but at the end of the day Catholics do not create problems, and are a minimal minority. As it were, it was a issue that could have been solved tomorrow or the day after tomorrow, without any urgency. If on the other hand the Holy See is a superpower, the thought process becomes: we Chinese, who must insert ourselves in this world, where the Vatican manages to be so important. We must have a sense of urgency.

Secondly, there is also a calculation of the risk involved. If the Vatican is so powerful, it is no longer just about administering a few million Chinese Catholics. These may perhaps help us, but they could even cause us harm in our position in the world. In this way the question has been put in totally different terms compared to how the question was thought of before.

The interview

From that point, the thought was born, and gently grew, of carrying out an interview with the pope which was supposed to be a message which the two leaders would exchange, and above all which needed to breach the confines too, overcoming the obvious profiles of the situation.[1] That is the pope, as he has shown, and as was already clear, was not simply interested in the fate of the Catholics, he did not only talk about Catholics; the pope, this pope, is interested in the fate of all 7 billion human beings, and he is greatly interested. He does not only think about his own pasture of a billion baptised catholics, he thinks about everyone.

This is very important because in that interview he spoke with the Chinese about the issues that are dear to the Chinese. He spoke as a priest, a good priest. He spoke like a priest, who as with a child – I remember – when trouble comes up, he could find the words that touch the heart and convince you to think back to what you did. This approach has convinced the Chinese too, and I think it has placed the China-Vatican question on different terms, not simply on ideological terms, not just geopolitical, but also on terms of human aid. There were things which the Church could do for individual Chinese who have many material problems but they also have very big problems of conscience, such as the one-child issue.

The Chinese adore their children, and children are a fundamental issue, the continuity of their ancestry, almost as though there is a religion of children, the fact that the Chinese have decided to just have one child for the past 30 years, to sacrifice, to kill “their God” in some way, in order to grow, to transform themselves, to change, is a testimony, on one hand of how determined they are towards change, towards puttings themselves on a different path.

On the other hand, the one-child matter is evidence of how much they have suffered and suffer from these changes, and the pope has succeeded in finding the words to look forward, not to torment himself and continue tormenting himself. So this was a very important thing, and I think the interview was very successful, so much so that, a few hours after the interview was released, the Chinese newspapers picked it up. It has been brought up hundreds of times. They did not translate it completely, but they gave it significant coverage.

A very important detail is that the interview took place in English, not in Italian, not in Chinese; English was the only official version because it served as a neutral language, which was understood by the pope and understood by Xi Jinping at the same time. It’s a crucial aspect, from my modest journalistic experience; translations are always a trick, always very delicate especially between Italian and Chinese and vice versa, culturally and structurally very different languages. Therefore, it is not about making mechanical translations, but about conveying a thought on one side and the other. And in this development of the thought, obviously a thousands of pieces are lost on both sides. So it was important to have a neutral medium that had the same value on one side and on the other, and English is a language that by now both the pope and Xi Jinping are able to understand without further mediation.

Sentimental Inspiration

This was the first point of rupture and of concrete approach, that is, the illumination which took place during September 2015 became a first act of important convergence. A second act, was a visit in March 2016 of the executive vice president of the party’s school who came to Rome, met so many people and “sniffed out” the situation and was amazed by the Vatican Museums, by the Culture and by their depth. Another very important element: he was intrigued by the fact that in the Vatican Museums there were many Chinese sculptures and works of art, because the Holy See considers these treasures part of the history of the Holy See and of humanity, and of the witness of the Holy See’s love for China.

“Love” is a rather strong word that is not used in geopolitics, yet a very important word for the Church and for China, a country which is politically very skeptical but also very sentimental. To face China it takes a sentimental inspiration and if there is this sentimental inspiration, so many difficulties are overcome; without this many difficulties instead arise and multiply; the perception of this feeling towards China was a very important element.

In those months Gianni Valente had interviewed some underground Chinese bishops for Vatican Insider. Everyone had expressed their support for an agreement with Beijing. That is: the Chinese Church most faithful to the pope during the decades wanted the agreement, it was not contrary to it.

All of this paved the way for an important intersection, which arrived in August 2016 when the Hong Kong titular cardinal, John Tong, published a long ecclesiological essay on the diocesan weekly which concretely opened up on the terms of an agreement between the Holy See and China. The agreement was not impossible, but there was a concrete space for the good of the Church in China that should no longer be left alone. The question regarding the bishops could be resolved.

Such a well-versed, human and authoritative intervention meant that there was in reality no substantial opposition to an agreement.

To act as an amplifier during those months and create a new consensus on this issue, even in China, there was then the work of the Global Times, the semi-official newspaper, born from a rib of the People’s Daily, voice of the Chinese leadership. The Global Times has published four articles,[2] quite a multitude in comparison with the past.

In August, for the first time in the history of their bilateral relations, Chinese President Xi responded to a pope’s message and sent a copy of the 7th century Christian Stele of Xi’an as a gift. It is to be highlighted that in the 60’s Paul VI had already written to Mao. Since then, all the popes, several times, wrote to the Chinese leaders, without any effect. For the first time, Xi responded with an object that meant: Christianity is not a Western religion that has recently arrived in China, but has been part of Chinese tradition for centuries, like the other great religion which is currently dominating in the country, Buddhism. Buddhism had arrived in China around the same time.

The speech of the Secretary of State

Another important date in 2016 was the speech by the Secretary of State Pietro Parolin for Celso Costantini. This was an absolutely fundamental speech for Beijing, because Parolin is naturally the Secretary of State and of course a man who has followed the case first hand, China’s case, for about twenty years, who has come to known the Chinese well and has conquered their trust working as a priest, rather than as a diplomat. He posed himself not as a politician, but as a priest, and this brought the interlocutors closer instead of pushing them further away. That is, he had emphasized a diplomatic political aspect but he had the essence of being a priest.

Why is Celso Costantini important? For two reasons, he first renounced being appointed cardinal by having a Chinese bishop appointed, for the first time, and this showed that the Church did not want to impose a control of the Roman clergy on the Chinese Church and indeed the Roman Church wanted the Chinese Church to be truly Chinese. Indeed it was important that the first Chinese cardinal was not him, since he was an Italian transplanted to China in the 1920s, but rather was a true Chinese. So it was a very important political message for China.

Secondly, extremely important from China’s political point of view, Costantini fought for recognition of the role of the Holy See with a first nunciature which was independently and far from France’s role.

The Catholic Church had essentially come out of China after the Jesuit order had been suppressed, we’re talking about the mid-1700s, after it had entered towards the end of the 16th century. It came back about a century later, in 1856 with the second opium war, brought over by France which was at that time the tutelary power of the church. In this context, with the example of Celso Costantini, Parolin wanted to affirm that the Holy See, even if it does not have a state like the papal state behind it, does not want to act on behalf of, or under a power which sought to dominate. So it was a very important message because naturally there is the debate in China: but on whose behalf does the Church act? is it acting for the new current powers? does it act to be helpful? is it pushed by the United States, Europe, Italy?

No, Parolin’s message is that the Holy See moves on its own and does not want power, it did not want it then it does not want it now. So the Holy See speaks for itself, it does not speak through the state, so this was a very important point to define, adding a political side.

The conference at the Renmin University

Another stage of this acceleration was a conference organized by the People’s University in Beijing on the 29th of October, at Renmin University. It is a somewhat peculiar university. There are three major universities in China, there are many large universities, but the University of Beijing is famous for history, literature, philosophy, humanities. Then there is Qinghua University, famous for the scientific subjects including economy, and Renmin University is the university founded by Mao Zedong, founded by the party, the People’s University which is particularly interested in political issues and law, the most sensitive issues.

Therefore, the fact that Renmin University held a conference on religious issues was extremely delicate and important. In this conference, the Chinese publicly expressed an absolutely important and fundamental part of the Church’s secular relations on a historical level. They said, attributing it to Parolin, and in this sense emphasizing the importance that the secretaries of state have in bilateral relations, that the Chinese leadership would accept the role of the pope in the appointment of bishops.

This, in Italy, in the West, today seems obvious. In fact we know that it has been very thorny for centuries. Even for us, the story of the bishop-counts is also one that shaped the relations between the Holy Roman Germanic Empire and the papacy. The German emperor kneeling before the pope in Canossa tells of history’s subsidiaries.

In reality this fundamental point had not been solved by the Jesuits even when the Jesuits, with von Shall or Verbiest, had become part of the imperial court as very important ministers of the empire. Yet despite the power and influence of these Jesuits, celebrated historically, they too had failed to obtain from the emperor the privilege for the pope to nominate the bishops.

This was because the emperor at the time held both political power and quasi-religious powers. Vice versa, with the adoption of Marxism as a state ideology, Chinese political power has become detached from the metaphysical dimension. The Chinese Communist Party is materialistic and has no interest in ultra-worldly matters. Hence a space for theoretical convergence opened up, which is very important because both systems work in deductive “theological” terms: first we need to set the principles and then draw consequences from the principles.

There is a space for a true, profound agreement, the party does not care about God, it is interested in human affairs. The pope, the papacy, the Church is interested in issues that the party does not care about, God. It really opens up the possibility of a convergence like never before between Chinese imperial powers and the papacy and the understanding of the particularity and of the originality of the Catholic faith.

The reasons behind a misunderstanding

There was the problem in China of a profound lack of understanding of the particularity of the Catholic Church, that on the one hand speaks Italian, speaks Latin, speaks English, etc., that is deeply rooted in the various national realities. But it is also universal and catholic, that is, precisely inclusive of everything, unlike Protestant or Orthodox churches which are much more rooted in local specificities at the expense of the general dimension.

This extremely significant step forward in understanding by China has taken place within a specific context. During October 2016, towards the end of the American electoral campaign, the Chinese interest in the Holy See issue was no longer internal but rather in relation to the whole international context. The international context naturally led to us focus on presidential candidates, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. Therefore many Chinese people thought that a Trump presidency would be better for bilateral relations, rather than a Hillary presidency.

In reality, after the elections, it was seen that this was not the case. Or possibly it would have been the same with Clinton, we do not know. But the Trump presidency has certainly led to a progressive, even very rapid, poisoning of bilateral relations. This has influenced the relationship with the Holy See because I believe that China has understood that the Holy See was not influenced by, and did not follow the Americans. It continued to maintain its strategic route regardless of what the United States could do, think or say. On the other hand, the power and influence of the Church continued to grow.

In all these months it seemed that the influencing power of the Church has taken on a new dimension. It also seems to penetrate some gaps left open by the American power that has its own problems of crisis and rehabilitation to a new world after about 16 disasters from the war in Iraq and Afghanistan, passing through the Arab springs and the war in Syria. Politics which have bled the American economy and deepened chaos in the Middle East and Central Asia.

The announcement of a possible normalization

This led to a small step forward, something which was very painful. On March 8, 2017, the Chinese aired a first television broadcast on the official network announcing the possibility of a normalization of relations. It was a very problematic thing. It was first supposed to be on one day, then on another, it was postponed. In the end it was done, and it was controversial. The Chinese said: but the Church has overthrown and helped to overthrow the communist regime, in Poland, it was the one that destroyed the Soviet Union, so, they implied, it would do the same thing in China.

In the transmission, it was objected, yes on one side that did happened, but perhaps this was also because in those countries there were specific weaknesses, and very strong weaknesses, of that system. But at the same time the Church in those years has saved Cuba, which in many ways could have been at a much higher risk than Poland or Russia. The Castro regime has been saved through a very strong intervention by the Catholic Church in favor of the Castros. This therefore shows that the Church has no ideological programs and no political agendas. On the contrary, it is proof that the Church looks at the world in broad terms and does not have an anti-communist prejudice. Certainly it is contrary to atheism, it wants more religious freedom, but it has saved Cuba.

This very heated television debate also highlighted the doubts and fears that continued to persist in China regarding this issue.

In this way, on the 1st of June there was another significant step forward. The cultural investment fund, led by Zhu Jiancheng, donated a painting to the Holy Father and the idea which we have seen developing, grew. We are talking about 2017; a joint exhibition has been planned, from the Vatican Museums’ side, in Beijing, and from the Museum of the Forbidden City’s side, in Rome at the Vatican Museums. The idea was launched put by them and then, recently, in November 2017 there was the announcement by Chinese television and the Global Times that the diplomacy of art is equivalent to the diplomacy which led to the normalization of relations between China and the United States in the 70s.

So this meant that in November 2017 we had the official “ice-breaking”, that is, the political declaration by China that there is the political will to normalize relations, of course they are not yet normalized but it was announced that there is the political will to do it – when they will be normalized and if they are -; these are open questions consisting in many details. We must develop the thousands of issues, even those of a diffident nature, thousands of fears of the two “administrations”, there is caution from both sides.

China needs to take into consideration ninety million party members, the stability and the risks that are increasing more and more day by day with tensions around China itself. On the other hand, the Church must think about how such a decision can be digested and lived by the rest of the Church around the world, among which there are Catholics, but not only, given the global influence on seven billion people.

A few days later there was a visit by the pope to Myanmar, a visit which was followed in great detail in China because the pope went very close to China. Myanmar is also one of the countries with which China has closer political relations. The pope addressed the issue of the Rohingya, who occupy an area where the Chinese might want to create their own port and strategic pipeline. Here the Chinese actually have a similar opinion with that of the pope and with the points of view of the majority of the American administration.

The Chinese hoped that the pope would support the country’s democratic leader Aung Saan Suu Kyi, they wanted to limit the power of the military. The Chinese have always had very close relations with Aung Saan Suu Kyi, indeed they have supported and protected them in very delicate times and are in favor of a positive democratic transition in Burma. Not only do they not want the military tyrants, but they do not want street clashes that tear the country apart. The pope managed to speak well, both to the military and to Aung Saan Suu Kyi, as well as to the Buddhists. In fact, in Myanmar there is a very radical and very anti-Muslim Buddhist fundamentalism.

The Chinese were very satisfied with this, so much so that for the first time the Global Times has dedicated an article to this visit by the pope, and a group of Chinese priests with a national flag went to the pope’s mass at the cathedral of Yangoon telling him: come soon holy father.

Of course, “early” in terms of Chinese times could be two months or two years, but now the important point is this acceleration. These days, it continues, despite, and perhaps in spite of the chorus of criticism that has arisen from a part of the international press against this eventuality.

Translated by Rob Rizzo sj.

[1] http://www.atimes.com/at-exclusive-pope-francis-urges-world-not-to-fear-chinas-rise/

[2] 2016/12/28 “Cautious optimism” over Sino-Vatican ties; 2016/10/25 Between God and Caesar; 2016/03/10 LitFest 2016; 2016/02/25 From Rome to Beijing.

Nessun commento